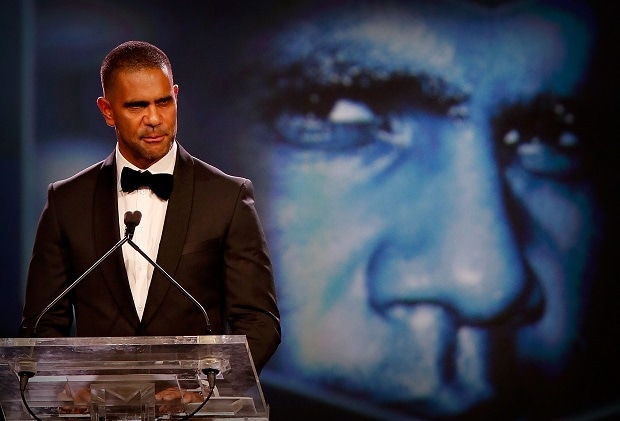

Michael O’Loughlin stood in front of the assembled who’s who of the AFL and told how football had changed his life. That he didn’t know where he would be without it.

Humble and gracious as always, the Sydney Swans champion said ‘thank you’ to those who had played a role in his extraordinary career as he stood centre stage at the Crown Palladium in Melbourne looking out on football royalty.

It was June 4, 2015.

But as much as O’Loughlin’s heart-felt words struck a wonderful chord with the football family, winning lavish praise throughout, this was more about the football family saying thank you to one of the game’s mega greats.

O’Loughlin, the shy, quiet Indigenous lad from Salisbury North in Adelaide turned 300-gamer and premiership hero, was inducted into the AFL Hall of Fame.

It was a very special occasion for the Swans as O’Loughlin joined this exclusive club on the same night former teammate and close friend Tony Lockett was elevated to Legend status in the Hall of Fame.

O’Loughlin had the crowd waiting on every word as he spoke of what the game meant to him, and how it had changed not just his life but the life of his family.

"I'd do anything for my family and being up here is a really special moment – not just for me but for them, for the sacrifices they've made,” he said.

"Playing in a premiership sits alongside that.

"I've been able to look after my family and my community and I'm really proud to say that if it wasn't for AFL football, I'm not too sure where I would be."

O'Loughlin credited former coach Paul Roos with a lot of his success.

"Sitting next to these champions of our game, the best game in the world, means a hell of a lot," he said.

"If it wasn't for Paul Roos I probably would've ended my career pretty early. Without his endorsement and his guidance and what he did for me, I probably would have really struggled to play, or get anywhere near, 300 games so I owe a lot to Paul Roos."

O’Loughlin was the first Sydney Swans player to reach 300 AFL games and only the third player of Indigenous heritage behind Gavin Wanganeen and Andrew McLeod to a triple century.

He was a member of Sydney's 1996 grand final team at 19, a key part of the Swans' drought-breaking 2005 premiership, and was named at full-forward in the Indigenous Team of the Century.

In an extraordinary career that began in jumper #38 in 1995, before he switched to #19 in 1996, he was All-Australian in 1997 and 2000, won the Bob Skilton Medal in 1998 and six times finished top 10.

He was the Club’s leading goal-kicker in 2000 and 2001 and, staggeringly, ranked top three on the Club’s goal list every year from 1996 to 2009.

He twice played for Australia in the International Rules series, and won the Fos Williams Medal as South Australia’s best player in a State of Origin match against Western Australia in 1998.

He retired at 32 in 2009 after 303 games and 521 goals, ranking third on the Swans’ all-time games list behind Adam Goodes (372) and Jude Bolton (325) and second on the Club’s all-time goals list behind only Bob Pratt (681).

Former teammates Mickey O' and Tony Lockett share a laugh at the 2015 Australian Football Hall of Fame Dinner.

But he was a reluctant Swan, as was widely reported amid the celebration of O’Loughlin’s Hall of Fame induction.

He’d grown up a huge Carlton fan, and idolised Blues champion Stephen ‘Sticks’ Kernahan. He dreamed of playing alongside Kernahan at Carlton, and even sharing accommodation with him.

Such was his fanaticism that at 17, ahead of the 1994 AFL National Draft, O’Loughlin decided he would ignore all approaches other than Carlton.

His dream was temptingly closer when he was contacted by Carlton recruiting boss Shane O’Sullivan.

“I had no idea how the draft worked, thinking it was as easy as them picking you and off you went. I just about had my bags packed because I was going to live with ‘Sticks’, not that he knew it,” O’Loughlin said at the time.

“Shane O’Sullivan kept speaking with me, telling me they were interested and would take me around the middle of the draft. Shane thought I would go around pick 40-41. Then Brisbane came around, so did Melbourne, then the Swans.

“Adelaide sent me a message saying they had been watching me play at Central District so could I fill out a draft form. It was meant to be attached but they forgot. Mum said they couldn’t be too keen if they forgot the form. We kept checking but there was nothing attached.

“The clubs who showed the most interest were Carlton and Sydney, and I just really hated the thought of going to Sydney. I saw them as a basket case.

“Their recruiting boss Rob Snowden came to meet us and I didn’t pay much attention to him because I was going to Carlton to live with Sticks.”

So the O’Loughlin family sat down to watch the draft, praying that Carlton would select Michael with pick 33 or 41.

Sydney had four picks inside the first 21 and went with Anthony Rocca, Shannon Grant, Stuart Mangin and Matthew Nicks. Carlton chose Scott Camporeale at 15 and Mark Cullen at 33.

This was massive. Cullen, from the Eastern Ranges in Melbourne’s TAC Cup competition, would never play an AFL game.

But more importantly it left the door open for the Swans to take O’Loughlin at 40.

“When they read my name out I was absolutely gutted, totally flat. I told mum I wouldn’t be going to Sydney but she said ‘no mate, you are going …. there’s nothing for you here’.

“Then Shane O’Sullivan rang and said good luck. I begged him to try and change the system.

“Then the Swans rang and I think I may have even hung up on them. I said I don’t think I will come. I moped around for a while until the first time I arrived in Sydney. I fell in love with the place.

“The first bloke I met after getting off the plane was Tony Lockett. Here I was going for a run on Coogee Beach with him, this legend. I couldn’t stop grinning.

“I went home that night and rang my mates and they thought I was bullshitting. Two years later I was playing in a Grand Final.”

O’Loughlin admitted a lot of people thought he’d only be in Sydney for a year or two and go back with his tail between my legs, but he was driven by a burning desire to prove them wrong.

Still, it was tough early. Homesickness prompted thoughts of quitting. But at the urging of his mother Muriel he stuck it out. Her tough, unwavering love was critical.

O'Loughlin also drew inspiration from teammates like skipper Paul Kelly, who "set the standard and was about digging deep and finding something when you're absolutely knackered".

The brilliant O'Loughlin was the only Swan to play in both the 1996 grand final loss and the 2005 triumph.

"It (the premiership) was the best day in my football life," he said. "Seeing our fans crying, that will stay with me forever. That's what this footy club means to me – we've been almost extinct a few times but we keep fighting."

O’Loughlin grew up in a tough part of Adelaide. His parents never married, so he was given his mother's maiden name of O'Loughlin, which came from her Irish great-great-great-grandfather. His ancestors were Czech Jews, Indigenous Australian (Kaurna and Ngarrindjeri), Irish and English. His paternal grandfather was a Czech-Jew.

It wasn’t an easy childhood, but while the football he kicked with his brothers and cousins was sometimes flat, there was always food on the table at home and a happy environment.

With 20-25 kids arriving every night for a game of kick-to-kick, he reckoned you had to be good just to get a kick.

Michael O'Loughlin has an incredible resume including AFL and Sydney Swans Hall of Fame status, two-time All Australian, premiership player, Club Champion and member of the Indigenous Team of the Century.

Widely known as ‘Magic’ or ‘Mickey O’, O’Loughlin began his AFL career as a half-forward/midfielder, but tendinitis in both knees in the early 2000’s caused trouble.

He hardly trained, often only completing stationary ball work on the training track, and joked that in his quest for fitness he swam and rode around the world many times over.

Initially his lack of condition caused soft-tissue injuries, prompting "a season or two" of self-doubt.

But he worked hard to add size and strength to his 190cm frame, honing in on his marking, and transformed himself into a permanent forward.

"It's those times when you're by yourself down in the gym and there's no lights, no cameras, no one around to watch you, whether you actually do the work or not," he said, offering a private insight that set a standard for those around him and those who would later follow him.

O’Loughlin, runner-up to Barry Hall in the Swans' goal-kicking seven years in a row from 2002, loved working in tandem with the premiership captain.

But he said it was “about making the most of your 10-15-20 possessions and making them really dangerous.”

"I loved kicking goals (but) it was always about 'how do I keep bringing other players into the game?' I was a big team player."

Indeed he was. And in retirement he still is. Having launched the GO Foundation in 2009 with Adam Goodes, he has worked tirelessly to encourage education, employment and healthy lifestyle among Indigenous people, and develop and empower the next generation of Indigenous role models in Australia.